James McRory Smith was a remarkable character. For over 30 years he lived in a remote bothy in the far north of Scotland. He cut himself off from society and clung to the wild periphery. But was he a truly reclusive individual seeking sanctuary in the great outdoors or simply an opportunistic bothy thief?

It is a question that has long divided hillwalkers and bothygoers. I met James only once and it was a meeting in the loosest sense of the word. Between us stood an old wooden door, the latch firmly down, barring entry to the tumbledown cottage he called home. There was no face-to-face contact, no pleasantries swapped, just anonymous confrontation.

On one side of the warped, weather-beaten boards slumped two exhausted hillwalkers seeking escape from the hostile elements in the only building for miles around. On the other, there was an angry old man unwilling to surrender his privacy. Reluctantly we tramped off across the bleak, unforgiving moor, fighting wind and rain, cursing the belligerent old sod as we hunkered down for a cold, sleepless night in the dunes of Sandwood Bay, a mile to the south.

At the time, I did not know the history of Strathchailleach or of its occupation. I was just angry at the rebuttal. But the incident sparked an enduring fascination with James McRory Smith and his life less ordinary.

Referred to by some as Sandy, James spent 32 years at Strathchailleach, one of the most isolated and primitive dwellings in Britain. There is no running water, no electricity and no telephone. The closest dwellings are six miles to the south, a smattering of crofts snaking west from the fishing port of Kinlochbervie. The journey in entails a long trek over pitted tracks to Sandwood Bay. From there, a rough and ready route must be negotiated through ankle-grasping heather.

For James, Strathchailleach lay at the end of a much longer and more tortuous trail. Born into a large family in Dumbarton his early years were spent in a cramped three-bedroom flat at Sandpoint. His father, Andrew Smith, worked for shipbuilders William Denny & Brothers, the town’s largest employers.

‘We were a large family,’ his sister Winnie Kilpatrick recalled. ‘The house we lived in was not big so it was difficult to get any time to yourself. James always was a bit of a loner, even as a boy. He was a deep, self-contained person.’

For James, brought up in a strict but loving family, a career in the shipyards awaited but events took a tragic turn when he was just 17. Without warning, his mother Elizabeth died.

‘I think mum’s death hit James hard. He left home a short time after the funeral and it was a few years before he was seen again,’ Winnie added.

Rather than enter the shipyards, James enlisted with the army, serving with the Black Watch during the Second World War. At the end of the conflict, he came home briefly but re-enlisted, returning to occupied Germany. Here James found love. According to an obituary printed in Am Bratach, a monthly magazine published in Sutherland, ‘He went back into the army which took him to Germany. Here it was he met the one woman of his life and, free to marry, they settled to share their life together.’

But this newfound happiness was short-lived. Details of the incident are sketchy but what is known is that his wife perished in a horrific car accident. With the two children from his marriage entrusted to the care of their maternal grandparents, he returned to Scotland, a broken man. He made no contact with his family, choosing instead a life on the road. He slept under the stars, or found shelter in bothies and abandoned cottages.

In the winter of 1962, he reached Sutherland. The north coast was close at hand; soon the ground beneath his itinerant feet would end. James found refuge in a former schoolhouse west of Durness and made a little money doing odd jobs on the Keoldale Estate. But there was resistance to his occupation of the building and he was pointed in the direction of Strathchailleach.

The cottage at Strathchailleach was probably built sometime in the 1840s. It first appeared on census records in 1851 and remained occupied by shepherds until the turn of the century. Thereafter there is only vague evidence of occupation suggesting the last permanent residents moved out in the 1940s.

The cottage was certainly empty in the mid-1950s when Bernard Heath, a stalwart of the Mountain Bothies Association (MBA), cycled from Sandwood Bay to Cape Wrath. Recounting the trip, Bernard described the cottage as ‘unlocked, clean and tidy.’

Occupying a shallow trough, it is built from rough stone and lime mortar. Back then, as today, it had an iron roof. Inside James found two main rooms and a small bedroom. There was no kitchen and no bathroom. All who had gone before him took their water from the Strath Chailleach river.

By today’s standards it was primitive, a hovel even but James quickly made it home. There may have been some rudimentary items of furniture, tables and chairs used by shepherds who occasionally stopped over. He wasted no time in adding to these, spending much of his time foraging through the flotsam at Sandwood Bay. Wooden fish and fruit boxes formed the basis for much of his furniture and they were a ready source of fuel for the fire. James also cut and dried peat from the moor.

The eastern room became his main sitting room while he slept in the backroom. His diet consisted largely of fish caught with a rod and line while snared rabbits and the occasional deer also found their way into his pot.

It was a simple life and James enjoyed few luxuries, other than cigarettes – his favourite brand was Capstan Full Strength – and a wee dram or a can of beer. High Commissioner whisky and Carlsberg Special Brew were his drinks of choice.

Content in his reclusive ways, James gave his own reasons for moving to Strathchailleach in a rare newspaper interview published in 1992. He said: ‘I enjoy the simple life. I moved to this area when I decided to drop out of the rat race. Now my life is perfect and I would like to stay here forever. Walking keeps me healthy and I reckon I’ve trekked thousands of miles to collect my pension and my messages. The only trouble is that I keep wearing out my wellies.’

There is little doubt he harboured a great love of the countryside. He spent many hours tramping the hills around the bothy and cultivated a keen interest in the birds and wild animals that were his only neighbours. He read, listened to the radio and painted; some of his murals remain to this day on the bothy walls.

Life at Strathchailleach may have been simple but it was lived at the mercy of the elements. Storms and blizzards could confine James for days on end while heavy snowfall rendered the weekly trek into Kinlochbervie for supplies an impossible task. For many years he survived unscathed, then, in the winter of early 1979, a fierce storm tore a hole in the west gable and he was forced to move out.

Enquiries were made after James failed to turn up at the Post Office in Balchrick to collect his pension. Over time it was assumed he had died and the June 1981 issue of the MBA Newsletter records that in June 1980, Bernard Heath and his wife Betty heard from police that James had not been seen for 18 months. They visited the bothy and found it in poor shape.

The MBA had been keen to take on stewardship of Strathchailleach, but James’ occupation prevented progress. Now, with him gone, the organisation drew up renovation plans. The December 1980 MBA Journal outlined the work required: ‘Rebuilding one gable end, repainting the roof and internal repairs.’

However, James was not dead. Word filtered back to the MBA that he had been squatting at Gorton bothy. His other movements during the 18-month period of absence remain a mystery but what is known is that he returned to the north only to be arrested. At Dornoch Sheriff Court he was sentenced to three months in Porterfield Prison, in Inverness, following a series of alcohol-related breaches of the peace.

There he managed to broker an audacious deal with the MBA that would enable him to return to Strathchailleach. According to Bernard Heath, within the uneasy confines of the prison visitors’ room, James lobbied for MBA support to repair the cottage.

‘The west room, floorless and often flooded, was to become, after major repairs, the open MBA bothy room. Sandy would have sole use of the best room with its open fire and his wee back bedroom as before,’ Bernard said.

In January 1981, the MBA agreed to proceed with the project on this basis, fearing that without intervention the cottage may be lost. A work party was scheduled for Easter 1981 and this proceeded as planned, with James playing an active role.

Strathchailleach finally took its place on the MBA’s bothy list but an update in the June 1981 Newsletter offered a hint of what was to come. It noted: ‘So for the time being the MBA is sharing Strathchailleach Cottage with Sandy. While he has never caused trouble, please let us know if any problems arise from this arrangement.’

Problems did indeed soon arise and worrying reports started to filter through to the MBA hierarchy, revealing members were being denied access. James had reneged on his word.

Stories told by those who visited Strathchailleach vary considerably; some were refused entry, while others found him to be very hospitable. The welcome given, or lack of, appears to have been dependent on James’ state of inebriation. Prolonged drinking binges were a common theme of his later life, suggesting he was not always entirely happy in his own company, far less that of others. An uneasy couple of years followed. Members planning trips to the area were warned they might not be able to use the bothy while efforts were made to negotiate a solution.

It is hard to say exactly why James went back on his word. Prior to the renovation, most visitors found hospitality rather than hostility at Strathchailleach. It is possible that following its addition to the MBA list, visitor numbers rose. There are other factors to consider too. James had experienced problems with outdoor activity groups, particularly wilderness survival courses aimed at the business sector. On more than one occasion, he found himself in conflict with these groups, as a conversation with Francis and Janet Whittington, who visited the bothy in 1994, revealed.

‘He said that they were a menace, wrecking the bothy and the bridge at Strathan. They had also set fire to one of his peat stacks,’ Janet recorded in her diary.

There were incidents where groups, struggling to live on meagre rations, ransacked Strathchailleach. This may have been one of the reasons why James had little respect for official associations, even if he did seek their help in times of crisis.

One of his closest friends, Sallie Tyzsko, said he considered Strathchailleach to be his home as he was there first.

‘He didn’t like any type of organisational body. The MBA did renovate the cottage and helped to maintain it. He needed them but at the same time, as far as he was concerned, it was his home,’ she added.

Some believe James made a promise he had no intention of honouring. There is no doubt the MBA was the only organisation that would have undertaken the renovation. Keoldale Estate had no use for the property and James did not have the resources necessary to undertake the repairs himself. His failure to abide by the agreement soured the relationship between the two parties and tarnished his reputation with many in the hill-going community. Resentment remains to this day.

With no amicable settlement on the horizon, the MBA was forced to admit defeat and, in 1984, Strathchailleach was dropped from the maintenance list. But James was not to live out his days there. In 1994, with his health deteriorating, he was forced to move into Kinlochbervie. Winnie Kilpatrick says he never settled there and in the spring of 1999, he was admitted to Raigmore Hospital, in Inverness, where he died on April 20, aged 75. Four days later he was laid to rest at Sheigra Cemetery.

Just as James’s life was ending, a new chapter was beginning at Strathchailleach; MBA volunteers completed a second major renovation in April 1999 and today the bothy continues to provide shelter to walkers crossing this far-flung part of Scotland. It also stands as a lasting memorial to the old man who, for over three decades, called the cottage home, weathering all the storms that brought with it.

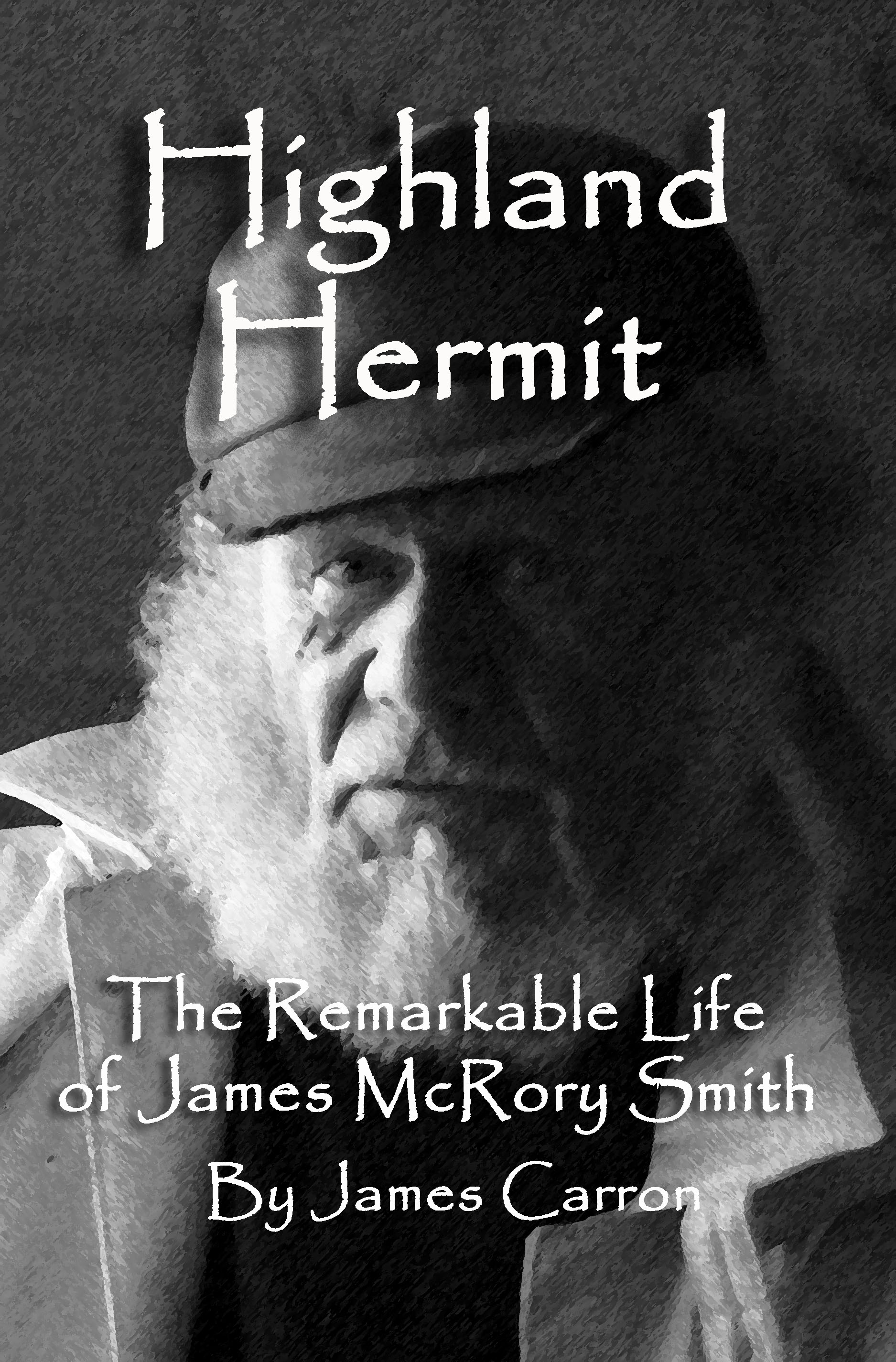

This article originally appeared in TGO magazine. I intend to upload more images of James McRory Smith and Strathchailleach shortly. Readers may be interested in a longer and more detailed biography of James McRory Smith, Highland Hermit, currently available as a paperback or an ebook.

This article originally appeared in TGO magazine. I intend to upload more images of James McRory Smith and Strathchailleach shortly. Readers may be interested in a longer and more detailed biography of James McRory Smith, Highland Hermit, currently available as a paperback or an ebook.

Fascinating story. I have lived in Balchrick for three years now but this is the first I’ve heard of James McRory Smith. Great reading!

Thanks for your kind comment. It is indeed a fascinating story, despite the fact there are still holes in my research into his life that I am always trying to fill.

Sadly, after a recent renovation carried out by the MBA, the period stone fireplace which needed replacing just one cracked stone, has been destroyed. The new one, built of brick, lacks the side niches of the former, where you could dry peat or your shoes of keep a kettle hot, it’s size is more or less 1/3 of the former and because the grate is raised only around 2 inches above the bottom, it is impossible to cook anything on the peat fire so even the old kettle remained only as a decoration. It has been turned into a decorative piece suitable for Kensington rather than NW Scotland, To me apart from reduced utility, it is ethnographic vandalism. The old fireplace did need a new chimney, because the old one leaked smoke into the roof space, but the new chimney did not need a new fireplace. Another part of Scottish history gone.

I stay at Droman just down the road from Balchrick. Having heard tales of ‘Sandy’ from the locals I went out to Strathcailleach to have a look. What a desolate and cleg-infested spot yet very beautiful particularly further up the glen and a lovely well-maintained bothy. Interesting to read the story of his previous life as I had heard various tales including that he had murdered someone and that his family had perished in a fire.Looking forward to reading your e-book.

Like all good stories, tales of James McRory Smith tend to grow arms and legs as they are shared over a pint or around the bothy fire.

An amazing story. Have just visited the area and walked to the bothy to try and get some insight-it’s about as remote as you can get, no clear path from Sandwood Loch and not on the way to anywhere. Spoke to someone who knew him and described him as “an alcoholic and a pest, who compelled locals to keep their doors locked because of his pilfering, and always took advantage of the people who offered him kindness and help.” I’m sure a lot more stories will come the authors way so I’m looking forward to a second expanded edition!

Just the other day, while staying on the Isle of Rum I bumped into an old boy who, during conversation about his travels, recalled meeting James in the 1980s. Slowly I am collecting further stories and recollections that will one day appear in a second edition. Thanks for your comments.

People have romantic visions of the ‘noble’ tramp, but if some drunken vagrant was squatting in your property, you’d probably have a different attitude.

James McRory Smith certainly had the ability to divide opinion. To some he was a character, to others a rogue and a tramp.

It’s nobody’s property Neil. All we really own is our skills and even then ur only as good as ur word. We’ve all been made to believe in ownership of possessions, really we just make use of these things while we’re here.

I read an article on this man in the Sunday mail sum 20 yrs ago. One can only admire him.

Who the fuck are you??? You’re talking about my uncle who gave up on the world through circumstance. You!!! Could not lick his boots. Come back to me.?

I’ve just finished reading the book Highland Hermit. An amazing story, also quite sad in that he felt the need to escape from life, although to me very appealing. The one question I was left wondering about was does anyone know what happened to his children? Did they ever know what became of their father?

I remember McRory from visits to Kinlochbervie and Sandwood 1969-1972. We didn’t call him Sandy or James. He was always said to be harmless, but his stalking about the moors at night was a bit spooky when I was camping. King, manageress at the Garbet Hotel, and the Hutchison family had lots of stories about him. Including his trip into Kinlochbervie just before Christmas one of those years to steal the cash in the church collection box. He was apprehended by police who arrived at the bothy by helicopter, thereafter spend a winter’s fortnight in jail, and was then despatched home with a new set of clothes and boots. Well done McRory.

Has Charlie Menzies contributed to this unfolding history? He knew him well.

When I was brought up in Scotland in the fifties the Catholic church were the biggest landowners in the country and their open congregation were the poorest in society and they had a plate for ( offerings). My thinking! Devious/manipulating and pious and that’s being kind.

Fascinating reading, many thanks.We’ve just got back from Strathan bothy. Have you heard of the Northways? Sad tale. The words ‘stop watching me’ and ‘**** off’ can still be made out on the bothy wall. http://www.mark-strath.blogspot.com

Pingback: Is this Britain’s most beautiful (and haunted) beach? | adcochrane

Utterly fascinating. I got here by way of a mention of James McRory Smith in Robert McFarlane’s The Wild Places where he describes spending a night in the bothy and wondering about what it was that kept Smith there for so long. I’ve been to Sandwood Bay twice but had no idea about the existence of this cottage. This beautifully written piece has stoked my curiosity even more. I’ll probably have to see the place for myself now!

I can identify with this man, being a bit of an oddball poet and misfit myself, with Asperger’s, and turning to the drink sometimes, so getting out of the social city into the natural world where we can be ourselves is attractive to me. I shall buy the book, and as I already have the hiker’s gear, hope that reading the book will inspire me to ‘break out’ into a much smaller wilderness in S.W. England, probably bivvy bag – but alone at night in autumn/winter when you’re 67 is not easy, so the ‘crazy’ McRory will hopefully inspire the ‘crazy’ me.

Would love to know the details of the caravan in Kinlochbervie where he spent his final years.

Pingback: A Caledonian Odyssey | Mini Adventures on Foot

I met Sandy one late afternoon in 1974 (I think). It was blowing a gale and I was seeking some temporary shelter as I heeded for Cape Wrath. It was early December. I had no idea that there was a resident in the bothy but I did notice smoke from the chimney. Sandy was cooking some fish he had caught and offered me a drink of “home brew”. Whatever was in the brew it certainly perked me up and I virtually flew up to Cape Wrath. I spent the night in the old coast guard house, no windows but otherwise very snug

An interesting story for sure, and as complete an account as ever likely to be. Thank you for posting. Like many, I’ve heard tales of ‘Sandy’ so was interesting to hear a balanced account of what was without a hard life. Many people dream of dropping out of society to some extent (he still drew a State Pension after all), then the reality slaps them in the face. I gather the second Highland winter is the breaking point for many incomers.

I’ve never visited this bothy, but having been to others and seeing the way some of their users treat them, (I’m constantly amazed that people who must at some level enjoy the outdoors think it’s improved by leaving their rubbish all over it) I can fully appreciate how anyone could get angry at experiencing it first hand. All the more so when it’s your home.

Thanks again, a good read.

The population was smaller in those days, Britain more stable. I fear the future will bring many more people looking to a bothy to ‘escape the world’, he just seemed to understand something and get there first.

As I live in the suburbs of a city, claim Pension credit, and have a taste for too much alcohol I suspect life near Cape Wrath is not for me! But I’ve known plenty of ‘oddballs’, and can identify.

Clifford.

I walked from Oldshoremore to Cape Wrath in September 1982. I was expecting to find an abandoned cottage at Strathchailleach, so I was surprised to see a curl of peat smoke coming out of the chimney. As I approached the cottage a bearded man (who I later discovered was Sandy) emerged from the gloom inside. He was shabbily dressed and wore a cap with a badge on it that read ‘The Captain’. I asked him where the best place was to cross the river, and he was moderately forthcoming. He said I could wade across near the cottage or go downstream where large stones made a dry crossing possible: “Depends how much ye want to cross the river”, he said.

I walked past a football pitch today and dozens of high end SUVs and performance cars occupied a further football pitch size area. BMWs, Mercedes, Porsches etc. A premier league training ground? No, some nondescrpit kids playing Saturday morning all driven there by their spoiling parents and needing a second pitch to all park their tanks. And some think this guy’s life was wierd? Not at all.

Thank you for this interesting insight. I live in Canisbay and the wild still calls to me although I can longer walk like I used to. What an interesting life story

James is my Uncle, my dad ( John Smith) told me many stories of them all (16 kids) growing up, it was a tough life and my father was tough with incredible survival skills and great knowledge on how to live off the land and how to treat many illnesses with plants which he passed on to me. I think most of the family were tough survivors. I still eat salt on my porridge as my father once told me that they didn’t have sugar in Scotland cos they were too poor and also “only English men and poofs have sugar on their porridge “